“We Too Dream America” – Racial Uplift vs. Art for Art’s Sake

February 14th, 2019

Richard Mayhew, Transgression, 2008, Oil on canvas, 50 x 60 inches

A guest blog by Rick de Yampert

Gaze at Richard Mayhew’s impressionist painting on exhibit at the Museum of Art – DeLand, and one will be blissed by its serene, bucolic swirls of oranges, yellows and lavender, and its bright greens suggesting a forest.

But viewers may be puzzled by the discordant title of Mayhew’s 2008 oil painting: “Transgression.”

However, the exhibition’s title, “African American Art: We Too Dream America,” signals that Mayhew is Black, and viewers – rightly or wrongly, accurately or not – may suspect that some sort of socio-political-racial commentary is at play in Mayhew’s name choice.

Perhaps the artist, who also is of Native American descent, believes he is making some sort of transgression against his heritage by not painting an “uplift the race” work with an explicitly African American or Indigenous American theme. Perhaps Mayhew believes he’s “transgressing” into an exclusionary “white” world of impressionist painting.

Or not. Perhaps the transgression at work in Mayhew’s piece is simply the feeling one gets when we humans step into nature, whether in real life or through a bracing painting such as this.

Art for art’s sake, art as “racial uplift,” art reflecting the brutal racism faced by Black people throughout U.S. history – such disparate approaches to African American art are not overtly addressed in “We Too Dream America.” But those conflicting approaches inform the exhibition and give it a compelling strength.

Diverse styles and media abound, from “Slave Boy,” a 1899 bronze bust by May Howard Jackson; to the cubist “Folk Singer,” a 1968 woodblock print by Samella Lewis; to the colorful “The Sleeping Lady and the Giant Who Watches Over Her,” a 1984 abstract expressionist acrylic by Gaye Ellington; to the huge, quilt-like “Jazz Stories: Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #1: Somebody Stole My Broken Heart,” a 2004 fabric-bordered acrylic piece by Faith Ringgold.

The exhibition also includes 16 works from the museum’s permanent collection by Purvis Young, an “outsider” artist from the Overtown neighborhood of Miami who one critic dubbed the “Picasso of the Ghetto.”

Patrons will find aesthetic pleasure in these works, quite apart from knowing anything about the artists’ backgrounds – their ethnicity or otherwise. Yet anyone with more than a passing knowledge of African American history and culture will ponder how the Black experience (or, rather Black experiences), racism, W.E.B. Du Bois’s “double consciousness,” and “racial uplift ideology” may, or may not, have played a role in these creations.

Albert Alexander Smith, W.E.B. DuBois, Undated, Watercolor on paper, 15 x 11 inches

“I could have thrown in some very harsh, really heavy-duty social realism and highly political work,” said guest curator Dorian Bergen, co-owner of ACA Galleries in New York City, which provided many of the exhibition’s works. “The struggle (of African Americans) is in there. Many of these works have a message in there, and you can find that message, but I wanted aesthetically beautiful works – to include the best examples by these artists. I just didn’t want guns and knives and blood. I wanted kids to be able to see this exhibit, to look at the art for the art’s sake.”

Pam Coffman, curator of education for the Museum of Art – DeLand, details two competing “philosophical ideologies” faced by African American artists in her introductory essay in the exhibition’s catalog: During the Harlem Renaissance, African Americans devoted to the racial uplift approach “supported the idea that the Black fight for equality should be championed by the artistically talented and culturally privileged African Americans whose works, inspired by racial heritage and experience, would validate the beauty of their race and its crucial contribution to American culture . . . .

“The second concept was in opposition to the elite art-as-propaganda view” and “argued against portraying only ‘cultured’ and ‘high-class’ African Americans who reflected the standards of White society. They believed artists should create work for its own sake.”

Those two conflicting ideologies continue to echo in the art, music and literature of African American creators even today, and they can be seen in the breadth of “We Too Dream America,” which features works that date from E.M. Bannister’s 1885 naturalist “Untitled Landscape” to Beverly McIver’s “Laughing with My Dad,” a 2018 expressionist duo portrait that exudes joie de vivre.

E.M. Bannister, Untitled Landscape, 1885, Oil on canvas, 8 x 14 inches

Kevin K. Gaines, the Julian Bond Professor of Civil Rights and Social Justice at the University of Virginia, addresses racial uplift ideology in an essay on the website nationalhumanitiescenter.org, noting that “The persistence of racial stereotypes and prejudice fuels the perception among many blacks that racist attitudes must be countered by positive images and exemplary behavior by blacks.”

That ideology is reflected in the exhibition by Aminah Robinson’s loose, carefree, joy-filled portraits of writer Maya Angelou, folk artist Clementine Hunter and sculptor Edmonia Lewis. The latter is virtually a poster child for racial uplift art: Hand-scripted writing on the mixed media work reads “Edmonia Lewis 1845-1890. First Black Sculptor in Amerika (sic), a pioneer in neo-classical work.”

Albert Alexander Smith’s undated, beatific watercolor portrait of sociologist, historian, civil rights activist and writer W.E.B. Du Bois might be considered a work of racial uplift just by the towering presence of its subject. In any event, Du Bois’ concept of “double consciousness,” articulated in his 1903 essay collection “The Souls of Black Folk,” very likely played in the psyche of every artist in this exhibition, and is worth repeating here: “It is a peculiar sensation, this double consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife — this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self.”

Striking examples of the art-for-art’s-sake “school” can be seen in that Mayhew work, the dancing, exuberant, O’Keeffe-ish colors of Gaye Ellington’s abstracts, Columbus Knox’s naturalistic “Haitian Dock Scene,” the triangles and hexagons of Al Loving’s “Yellow September” and the nervous energy of Purvis Young’s street scenes and his Don Quixote-like “Two Leaders.”

As Bergen noted, there is no “heavy-duty social realism” or “highly political work” in “We Too Dream America,” which takes its title from Langston Hughes’ famous, faintly ominous poem “I, Too.” The closest the exhibition comes to that is with “Target,” a 1992 lithograph by Emma Amos that depicts a farm laborer in orange silhouette and positioned in the concentric rings of a target. Its motif recalls the raucous, agitprop rap of the hip-hop group Public Enemy and its logo – a silhouette of a Black man caught in the sight of a rifle’s scope (and crafted several years before the Amos work).

The inclusion of even just a few more similar, provocative socio-political works, such as, say Faith Ringgold’s harrowing 1967 oil painting “American People Series #20: Die,” would have amped up “We Too Dream America” and made the exhibit even more riveting than it already is.

And what about a piece that “merely” portrays a Black face or faces — do those constitute a “racially uplifting” work, or are they art for art’s sake? What about such works here as “All the Things You Are,” Romare Bearden’s frenetic 1987 watercolor and collage of a sax player – a work that may be the closest that be-bop jazz has ever come to being captured visually?

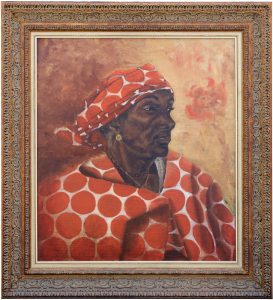

What about the contented faces of the construction workers in Jacob Lawrence’s 1972 lithograph, “Builders #1”? What about the stoic face of Laura Wheeler Waring’s 1940 oil painting “Woman Orange Scarf”?

Laura Wheeler Waring, Woman Orange Scarf, 1940, Oil on canvas

What about Ringgold’s previously cited “Jazz Stories: Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #1: Somebody Stole My Broken Heart”? That work — literally and figuratively larger than life – may serve as a metaphor for the entire exhibition: The title tells us the singer’s heart is broken, yet with eyes closed and arms held wide, she sings in ecstasy, the very embodiment of the May Angelou poem “Still I Rise.”

Perhaps that question – racial uplift or art for art’s sake? — is best left to art historians, sociologists or scholars concerned with the dynamics of America’s black-white racial divide. Meanwhile, viewers of “We Too Dream America” will be mesmerized regardless of these creators’ motivations.