Sandy Winters creates bizarre, organic and mechanical worlds in “Creation and Destruction”

February 19th, 2019

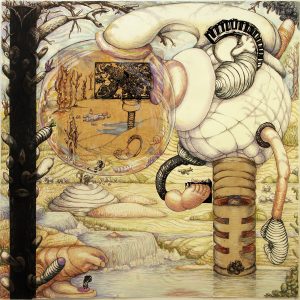

Sandy Winters, Conveyor Belts and Crystal Balls, 2017, Flash acrylic, graphite, collage with block print and newspaper on Arches cover stock paper, 52 x 72 ½ inches

A Guest Blog by Art Critic by Rick de Yampert

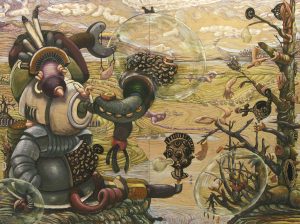

The painting “Seven Deadly Sins” by artist Sandy Winters depicts a robotic contraption that’s either devouring, or perhaps generating or creating, what looks to be human brains.

Meanwhile, a strange tree to the right sports human arms, and again one must ponder whether this macabre scene depicts the horror of severed arms hung on branches, or quite the opposite: Perhaps the tree is regenerating those body parts and bringing them to life.

Look closer at the 6-by-8-foot oil painting, which is part of the exhibit “Sandy Winters: Creation and Destruction” at the Downtown Gallery of the Museum of Art – DeLand through March 24, 2019, and you see more going on.

In the painting’s background, a panoramic vista of some quasi-alien landscape, one can discern a line of tiny, bizarre, bug-like creatures marching in single file, while nearby two of them seem to be battling each other in a death match.

“I’m really interested in the nature-culture clash,” Winters says. That theme plays throughout the 46 fantastical works of “Creation and Destruction” as Winters morphs mechanical objects with strange plants and bodily organ-like objects and casts them in vast, detailed, busy, arcane scenarios.

Such a clash might lead to grim, even sinister depictions, and indeed Winters’ sci-fi-like scenes can resemble modern interpretations of Hieronymous Bosch’s medieval-era “The Garden of Earthly Delights.” However, Winters’ style exhibits some of the low-art insouciance of underground comics artist R. Crumb, the zaniness of a Rube Goldberg machine and the flamboyant, playful surprise of Dali, Joan Miro, Max Ernst and other Surrealists.

The result is a body (pardon the pun) of work that is at once disturbing and bizarre but also, well, fun in a way that recalls some sort of wacky mad scientist with a painter’s palette and easel.

During and after obtaining her M.F.A. from Cornell University in 1977, Winters painted portraits and, she says, became “very good” at it. But the direction of her art changed when she began spending time in gardens.

“I started to see how plants are so anthropomorphic,” she says. “Vegetables at the markets started to look like masks, and that was when I was listening to mythology, women’s roles in mythology, the Dionysian myth, so all of these plants started taking on this kind of primordial, mask-like imagery.”

Over time, her plants “became more bomb-like, more torpedo-like,” Winters says. “Then they started to get feet. Now they’re starting to look like robots, so they’re half human, half vegetation.”

Meanwhile, she began to see the linear forms in her collage works as “representing architecture – humans’ attempts to structure nature.” The two sides, the human and natural worlds, merge in the artworks of “Creation and Destruction” so that “sometimes nature and plants are winning out, and sometimes humans are being destructive and the cubist collage is winning out, the architectural form.”

Winters insists her art is not overly grim. She sees dark humor and even whimsy at play in her weird scenarios.

“I depict an environment of largely abstracted organic and mechanical forms, which, if I have succeeded, are forbidding and yet playful, inexplicable and yet evocative, indeterminate and yet on a subliminal level intimately familiar,” she says.

As if to occasionally amplify the whimsy aspect, on occasion Winters will — akin to the alien bugs of “Seven Deadly Sins” — cast tiny creatures into her scenes. Marching elephants and what appears to be a dismantled Tin Man from “The Wizard of Oz” can be spied in “She Takes You Down the River,” a 2007 acrylic, watercolor and graphite work on paper. “Bring ’Em On,” a 2007 oil, aluminum, graphite and print work on wood, includes a ring of small elephants and a procession of strange animals and a toy tank.

But the foreboding has its day in Winters’ work, too.

When she says she hopes her work will be “on a subliminal level intimately familiar,” they are – but in a squeamish, unsettling way. So many of Winters’ many organic-looking entities make us seem like voyeurs who are witnessing our own internal organs that have been hijacked and put on display. The phallic shapes in “Conveyor Belts and Crystal Balls” flip the Medusa myth and, instead of feminine danger, they conjure an image of male menace. The amoeba-like entities captured in a giant glass globe in “Devil’s Hair Cut” seem threatening precisely because they’ve been quarantined.

Marshall McLuhan’s famous adage that “the medium is the message” has a place in Winters’ art: Her mediums include oil, acrylics, graphite, collage and block prints – and one of her favorite techniques is taking a small block print or graphite drawing and extending its boundaries on a canvas in every direction to create a new, huge painting. Such “seed” works are easily discernible in any number of the larger works of “Creation and Destruction.”

And so it is that Winters’ process (her medium) resembles her content (her message): The sprawling, organic worlds she depicts are created by a sprawling, organic process.

As Winters notes, her worlds can seem at once both ominous and whimsical, both alien and familiar. Viewers likewise will face a duality: They may have the impulse to flinch and turn away, but Winters’ bizarre, surreal worlds will inspire a curiosity that will have them looking back again and again.