Purvis Young: The Poet of Overtown Bearing Witness

June 16th, 2020

By Pam Coffman

Curator of Education, Museum of Art – DeLand

The Museum of Art – DeLand is proud to maintain a permanent collection that represents world-class artists of all strata of society. Perhaps one of the greatest highlights of the collection is the work of iconic African American artist, Purvis Young, whose story of redemption and devotion to his community is as remarkable and moving as the pieces he produced.

The following is a previous essay written by Pam Coffman, Curator of Education, for an exhibition of Young’s work at the Museum of Art – DeLand. In light of the manifest struggles still persistent in our society, we have found that Young’s work, his words, and his visual storytelling ring truer than ever today.

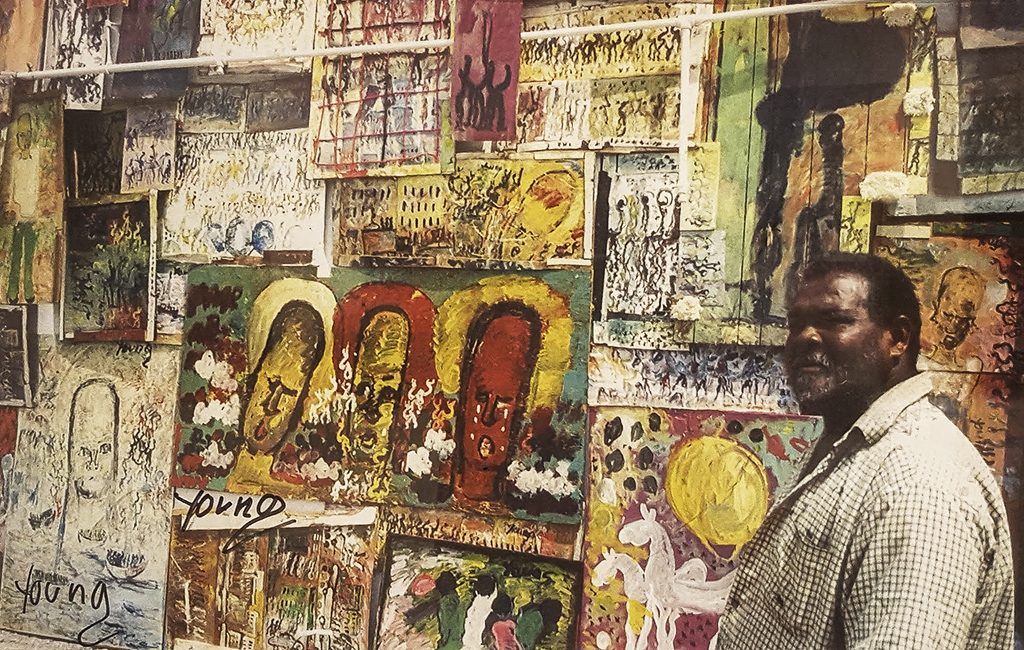

“For so many years, people have been calling me all different kinds of names to describe me as an artist, outsider, black artist, ghetto artist, the Picasso of the Ghetto. I just want to be called an artist. That’s all I’ve been doing all my life is painting.” Forty years and thousands of paintings, drawings, and sketchbooks attest to Purvis Young’s compulsion and calling as an artist. A calling that as Purvis recounts, came one night in a prison cell where he was serving a sentence for breaking and entering, “I woke up and the angels came to me and I told ‘em, you know, hey man this is not my life – and they said they were gonna make a way for me, you know….” The way led Purvis Young back to his home in Overtown, a once thriving center of African American life and culture in Miami reduced to a few square blocks of decay, despair, and devastation. It was this place and its people – his people that provided the inspiration, stories, and materials for Purvis Young’s visionary art works that bear witness to his anger and frustration, but also to his hope and belief in a better future for generations to come.

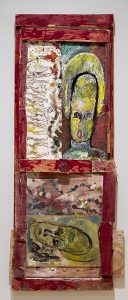

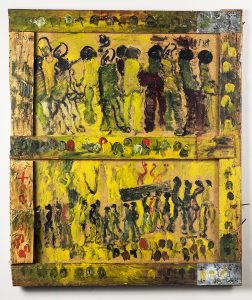

Motivated by the 1967 Wall of Respect mural project in south side Chicago, Purvis began his own visual chronicle of life in Overtown by painting hundreds of pictures and putting them on abandoned buildings in Good Bread Alley. His “canvases” were bits and pieces of cardboard, old plywood, broken furniture, scraps of fabric, discarded books, rusty nails and hardware, used carpet, and other assorted debris collected from the streets of his community. These works did not hang unobtrusively on the buildings. They jutted out from the surface infringing on the passerby’s space, their textures, colors, and bold rhythmic shapes demanding notice. Whether by necessity or plan, the physical elements of Purvis Young’s artworks were a commentary on and a re-visioning of the destruction of his community.

The Good Bread Alley project brought public attention to Purvis and his artwork and collectors such as Dr. Bernard Davis and the Rubell family became his patrons and advocates. At one point, the Rubell’s bought the entire contents of his studio – about 3,000 artworks. Their generous gifts of Purvis Young’s work to several major art institutions helped ensure his place in art history. Other early supporters of the artist were Barbara Young and Margarita Cano from the Miami-Dade Public Library System. Purvis, who had dropped out of school after 8th grade, spent countless hours at the public library pouring over books about his favorite artists including Rembrandt, El Greco, and van Gogh. It was Purvis’s intense passion for knowledge that attracted the attention of Young and Cano, eventually garnering him several commissions for public library murals. They also provided Purvis with discarded library books that served as sketchbooks for his endless ideas and drawings.

Although Purvis Young’s artwork began to be shown across the country, his world remained focused on the people, streets, and abandoned buildings of Overtown. It was only late in his career that Purvis traveled outside his neighborhood and began to realize the impact of his life’s work. The one driving and constant factor for over forty years of his life was always the work. Purvis would spend 10-15 hours every day painting, resulting in a prodigious output of art. Asking Young to stop painting would be like asking him to stop breathing. Even when his health became critical, he still went to his studio and painted. Admonished by various dealers to enhance the value of his work by painting less, Purvis’s response was “people don’t say that birds fly too much, that Shakespeare wrote too much, or that opera singers sing too much. But it don’t bother me that they say I paint too much, I just paint what I see and feel.”

In the tradition of the West African griot, Purvis Young was the historian, spokesperson, storyteller, poet, warrior, praise singer, and interpreter bearing witness to the suffering, survival, and resilience of his people and community. The only difference was he spoke with images instead of words and songs. Coming face to face with one of Purvis Young’s paintings, the viewer can’t escape the compelling and relentless power of this creative force. When talking about his work Purvis said, “I make like I’m a warrior, like God sending an angel to stop war, like in my art.”

Angels and warriors along with horses, buildings, pregnant black women, trucks, trains, railroad tracks, jazz musicians, large blue eyes, funeral processions, and crowds of calligraphic black figures inhabit his paintings and sketchbooks. The recurring images are as palpable as Purvis Young’s anger at injustice and his fervent mission to bring public attention to the political, social, emotional and economic plight of the people of Overtown. Each image functions as a symbolic element in Young’s visual vocabulary. The large floating oval heads represent angels and the good people. Horses galloping across the surface signify freedom and the slow-moving trains a chance for escape. Railroad tracks allude to the isolation and division of the community from the thriving life a few miles away in Miami. Skewed buildings painted in claustrophobic proximity speak of the decay and sense of imprisonment by the ravaged neighborhood. Large, ever watchful blue eyes are constant reminders that “Big Brother” and the white power structure are always hovering close by. Pregnant women, jazz musicians, and black figures vibrating with energy and life provide a glint of hope in the presence of so much adversity. Each artwork is a wordless poem, a song sung without sound, a piercing cry that reverberates from the very heart and soul of the artist.

If you could “hear” a Purvis Young painting there would be a cacophony of sounds from the emotional refrain of despair in Negro spirituals, to the lively, spontaneous rhythms of jazz, the often harsh and brutal beats of early hip-hop and the angry frustrated rhyme of rap. Purvis Young was a man of few words, but his work continues to bear witness and serve as a legacy to all people trying to make their voices heard. Novelist, Jane Rule wrote that “every artist seems to me to have the job of bearing witness to the world we live in. I think of all of us as artists, because we have voices and we are each of us unique. ” This is certainly true of Purvis Young, who “just wanted to be called an artist.”